Introduction to Probate

An estate executor is someone legally responsible for winding down and distributing a deceased person's estate. Some states refer to the executor as the "Personal Representative", or the "Administrator", and if the deceased person had established a trust, you will instead be the "Trustee". To keep things simple, we will just refers to all of these roles as the "Executor".

Serving as an estate executor can be challenging, and for many of us, it will be the first (and only) time we do it. We want to make the process as painless and as simple as possible, providing you with the best assistance.

Explore With Our Quick Links

Executor's Guide

Helping You Get Started

When a parent or someone close to you passes away, it can be a trying experience. In addition to dealing with natural feelings of grief, there are a number of practical matters that need attention: funeral arrangements, obtaining death certificates, reading the will, probate, distributing assets, and so forth.

This guide explains key responsibilities and tasks associated with the death of a loved one, with an emphasis on the duties of the estate executor (also known as the personal representative).

While this guide is not intended to provide legal or tax advice, nor to provide exhaustive coverage for all possible situations, we hope you will find it useful and helpful, as many others have before you.

Work With Us

The Basics

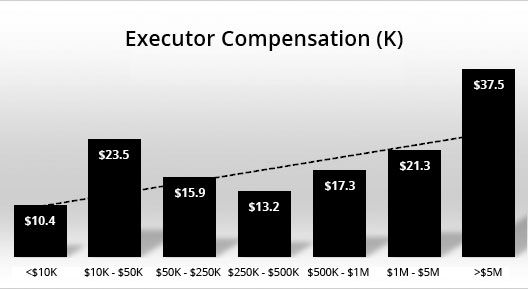

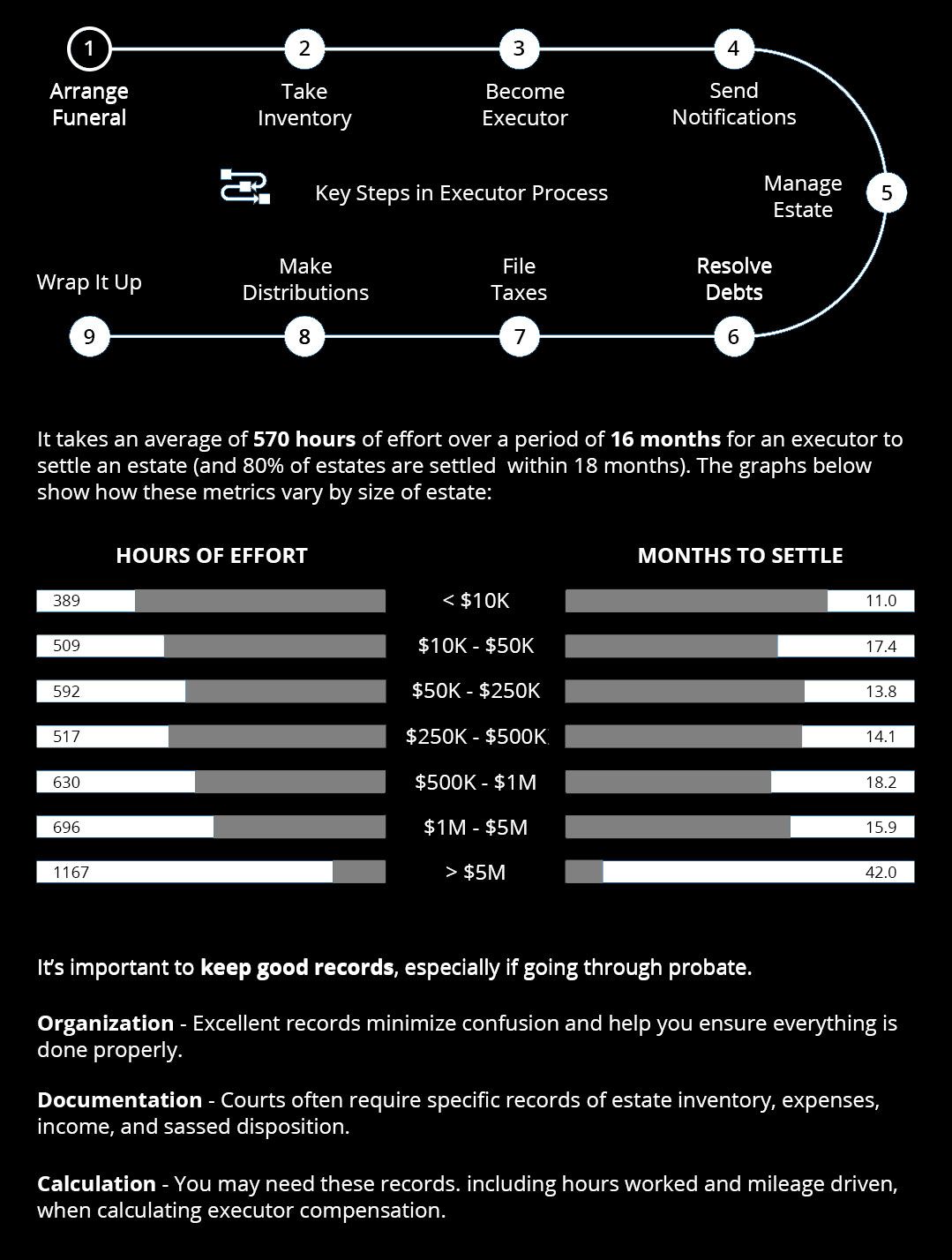

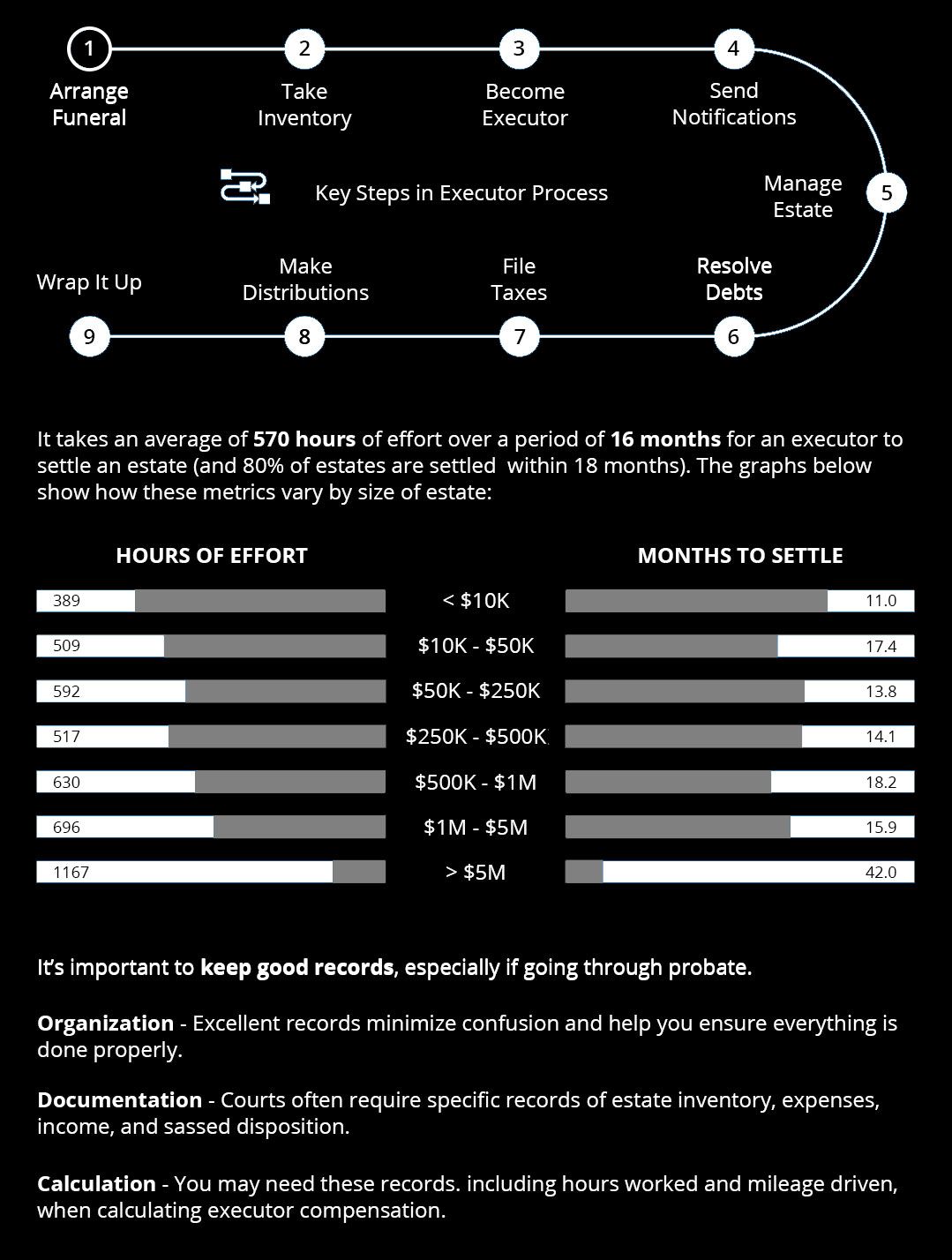

Fundamentally, it is the executor's responsibility to manage and wind down the deceased person's estate, resolving any debts, distributing assets to heirs, and filing legal paperwork. A somewhat simplified view of the overall estate settlement process consists of the following overlapping steps:

- Arrange Funeral — Request burial or cremation, organize memorial, order death certificates, etc.

- Take Inventory — Find and organize all estate assets and debts

- Become Executor — Get appointed by the court (if going through probate)

- Send Notifications — Notify friends and family, social security, banks, credit cards, etc.

- Manage Estate — Maintain and care for assets; plan asset disposition

- Resolve Debts — Pay off debts in full, or arrange for debt forgiveness

- File Taxes — Submit relevant tax returns: decedent income, estate income, inheritance, etc.

- Make Distributions — Distribute net assets to heirs

- Wrap It Up — Finalize the estate settlement, including probate final accounting (if applicable)

At multiple stages along the way you may have to file legal and tax paperwork, and while we will supply relevant information, it may be helpful to work together with a lawyer.

Like so many things in life, being an executor can become an all-consuming activity if you let it. While individual circumstances sometimes require significant effort, this guide is designed to help you through the basic process, and to organize the relevant information to make it easier for you and everyone involved.

Duties by Time Period

| In Advance | Get contacts, obtain copies of important documents, etc. |

|---|---|

| First Week | Notify close friends and family, arrange funeral, order death certificates, etc. |

| First Month | Notify social security, decide whether to hire a lawyer, etc. |

| First 3 Months | Notify insurance companies, open estate account, begin probate, etc. |

| Calendar Year | File annual property and income tax returns |

| General Tasks | Pay off debts, pay estate taxes, plan asset distributions, etc. |

| Final Tasks | Make distributions, finalize probate, close estate account, etc. |

Some tasks can be performed by anyone, such as notifying next of kin, while others have strict legal requirements. For example, some states require that an estate executor (or personal representative, or administrator) reside in the decedent's state, although many jurisdictions allow you to get around that posting an executor bond or by hiring an inexpensive local agent.

The Estate

An estate consists of a person's assets (e.g., house, bank account) and debts (e.g., mortgage, credit card balance). It can be helpful to think of an estate as the sum of:

- Assets Subject to Automatic Transfer: Certain assets, such as life insurance policies and IRAs, transfer automatically upon death to named beneficiaries. As an executor, you have no control over such transfers, but you may be still be helpful in the process, and such assets are considered part of the estate for tax purposes. If no beneficiaries have been named, then the assets end up transferring to the estate itself, and must be settled by the executor along with the rest of the estate.

- Trusts: An executor also has no control over trusts the decedent previously established (unless you also happen to be named a trustee of the trust). In general, living trusts are considered part of the estate for tax purposes, while bypass trusts are not.

- Other Items: Everything else is your responsibility, and must usually be settled via probate or a small-estate settlement procedure. If the will requires you to establish a new trust (i.e., a testamentary trust), the assets intended for the trust must first go through such a settlement procedure.

Probate

Probate is the court-supervised process of administering and settling a decedent's estate. Not all estates need court involvement, and this guide can help you figure out the requirements for your estate. In general, an estate will have to go through probate unless it contains only assets that automatically transfer to named beneficiaries (such as IRAs), or if the estate qualifies to use one of the state-specific small estate procedures. Regardless of whether or not probate is required, settling an estate requires a fair amount of effort, and we can help guide you throughout the process.

Distribution Priorities

When distributing estate proceeds, you must be sure to satisfy its obligations in a defined priority order. Certain transfers (such as to IRA beneficiaries) happen automatically outside the control of the estate, and the estate itself must then ensure it has enough funds to pay all taxes, then to pay estate administration costs, then any family entitlements, then any general debts, and with anything left over, fulfill any bequests, and finally distribute the residuary estate. If the estate runs out of money handling one priority, then subsequent priorities are left with nothing.

Note that state law determines which debts have priority over other debts, and some debts (such as funeral expenses) often have priority over family entitlements, but these specifics really only matter if the estate cannot pay all its bills.

Record-Keeping

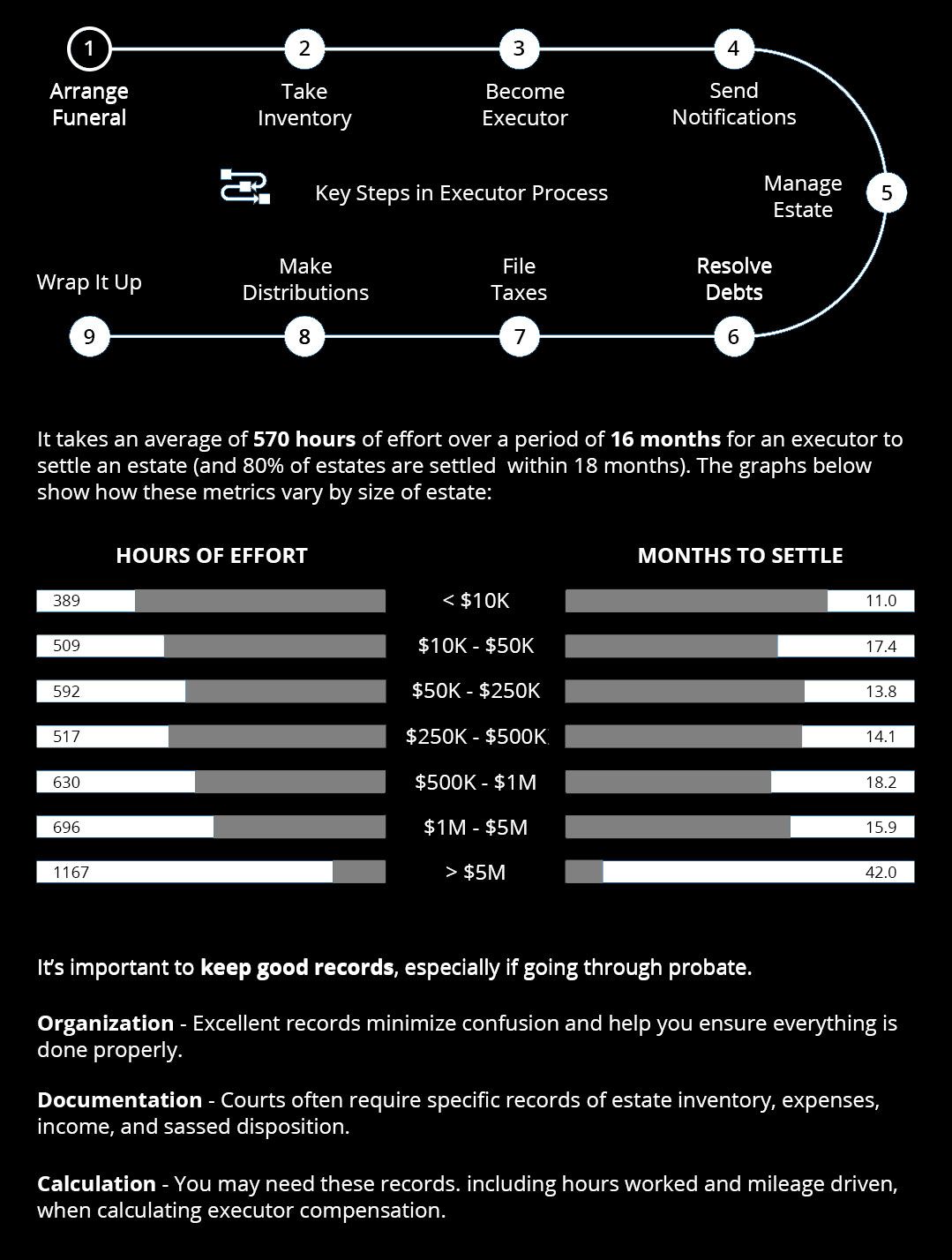

It's important to keep good records during this process, as you may need to account for your actions to the court or to other heirs.

What is an Estate Executor?

An estate executor is a person responsible for settling a decedent's estate. Often the estate executor is an adult child or other close relative of the decedent, but may be a professional lawyer, just a friend, or in fact, anyone named as executor in the will or appointed by a court.

An executor is also sometimes referred to as:

- Executrix: The term "executrix" may be used when the executor is female.

- Administrator: If the decedent died without a will, the court-appointed executor is known as the estate "administrator".

- Personal Representative: A number of jurisdictions, particularly those that have adopted the Uniform Probate Code, now refer to executors using the broader term "personal representative".

To keep things simple, we'll just use the generic "executor" term.

At the highest level, an executor is responsible for managing and winding down a decedent's estate: discovering, protecting and managing the assets of the estate, filing required legal paperwork, resolving debts, paying any applicable taxes, and distributing the net assets to the heirs in accordance with the will, or in accordance with applicable statute if there is no will.

An executor has a fiduciary duty to fulfill those responsibilities with the best interests of the estate in mind, to follow all applicable laws, and to act with the highest ethical standards. An executor is not required to be perfect, however; most states require that an executor simply follow the standard of a "reasonable, prudent individual".

See Key Duties for more information about an executor's overall duties. See also Timeline for a discussion of executor tasks by time period, and Executor Checklist for a quick list of standard tasks.

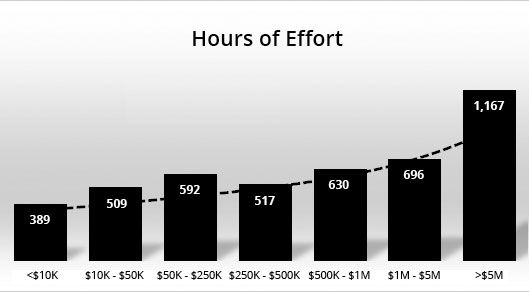

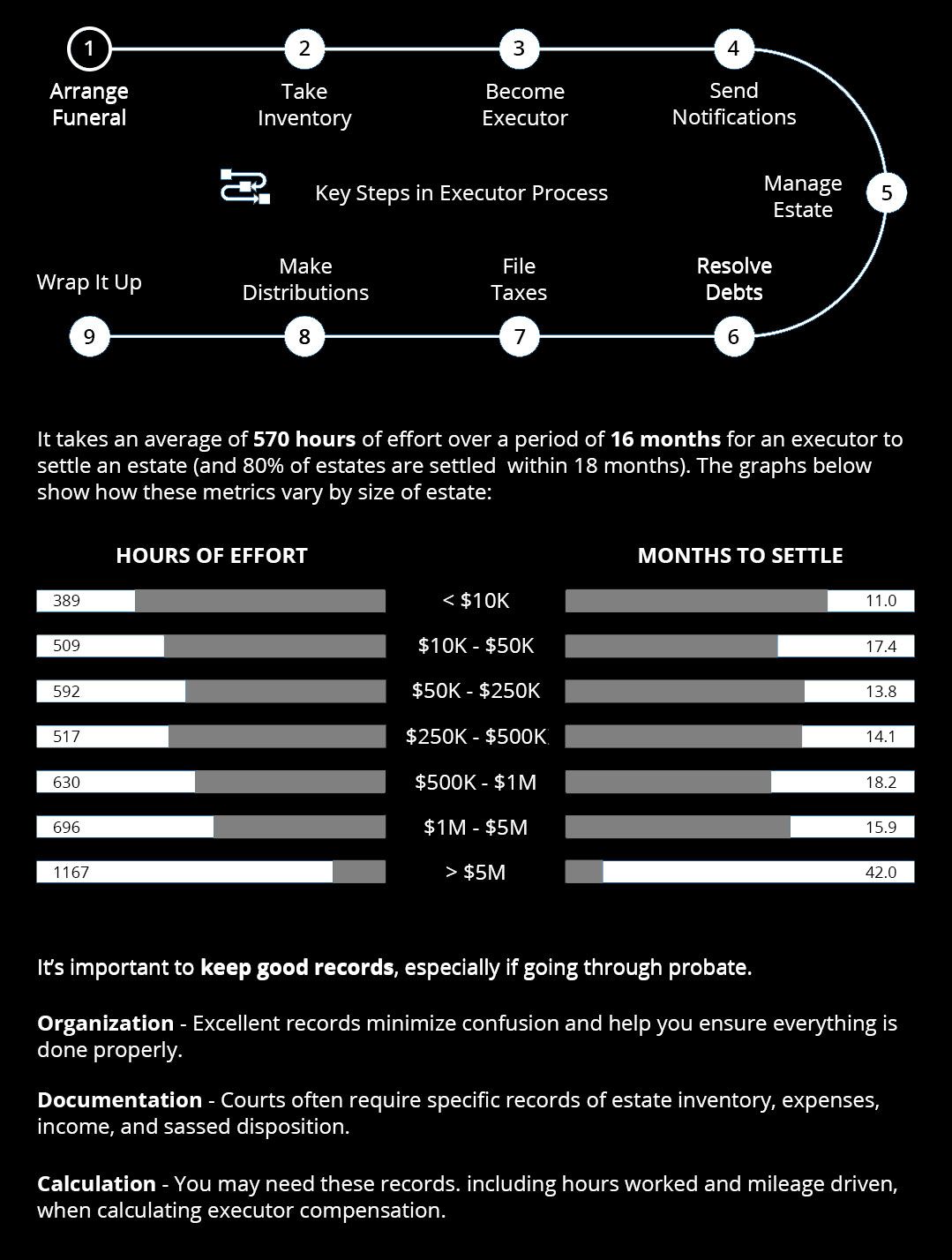

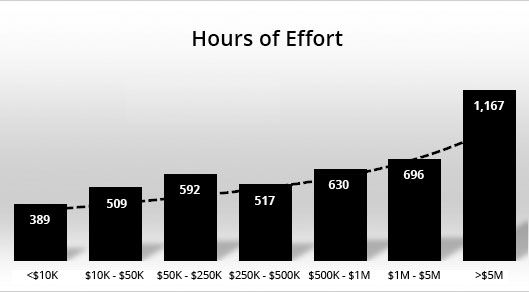

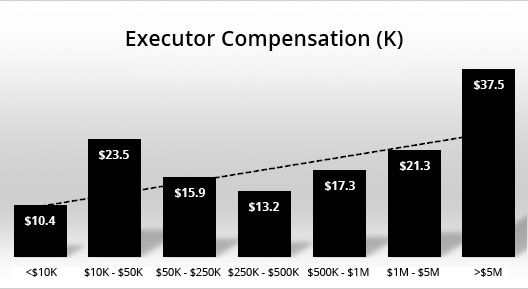

Serving as an executor usually requires significant effort: on average it takes 16 months to settle an estate and requires 570 hours of work (this effort varies somewhat by size and complexity of estate). See General Statistics for more information.

The role of estate executor comes with an element of financial risk.

An estate executor can be fined by the courts or sued by other parties for failing to properly fulfill his or her duties. You can be sued for anything, of course, but legitimate grounds for lawsuits include failure to act in a timely manner, failure to adequately protect or manage the assets, failure to follow terms of the will (note that following the terms of a will may not always be appropriate or even possible), engaging in illegal activities, and more.

Executors can be held personally liable for mistakes that result in losses for the heirs. Courts often require an executor to post a bond that will pay to cover any damage he or she may cause an estate (although such bond requirements are often explicitly waived in wills).

Even if the heirs aren't harmed, mistakes can still be costly. For example, if an executor distributes assets before the entire settlement process is complete, then discovers that there are not enough remaining funds to pay taxes owed (see CPAJournal article) or to pay remaining debts, the executor may be personally liable for fulfilling the remaining obligations (so best practice is to distribute assets only after all other obligations have been met; see Making Distributions).

Finally, note that executors may sometimes have to outlay personal funds to cover estate expenses until they can be reimbursed from the estate (because the executor does not yet have legal access to estate funds, or because estate assets are not liquid, such as the case in which an estate consists entirely of real estate).

Because serving as an executor is so time-consuming and does involve some element of financial risk, executors are generally compensated for their efforts. Laws and accepted practices for this compensation vary dramatically by state and sometimes even local jurisdictions, sometimes being expressed as a percentage of the estate, sometimes calculated in terms of effort expended, and frequently considering additional factors (see Compensation).

Sometimes a will names multiple people as co-executors, sharing the burden but also potentially making decisions a bit trickier since all executors must agree on actions.

In some cases an executor decides to step down during the process, or is removed by a court, or passes away him-or-herself. In these cases the alternate executor named in the will, or an executor appointed by the court, will take over.

Usually compensation is split among multiple executors, often according to effort expended, but some states have specific rules for handle compensation of multiple executors (see Compensation).

Sometimes a person writing a will names an executor in advance, and discusses that option with the named executor (who presumably has a chance to investigate the ramifications and accept or gracefully refuse the offer): see Choosing an Executor.

Sometimes a person writing a will names an executor in advance, and doesn't inform the target person, so the named executor is surprised upon discovering the assignment in the will.

In either case, most states allow a proposed executor to reject the role and step aside if, when the time comes, they decide they would rather not assume the role.

Someone must fulfill the role, however, and the court will appoint someone if no appropriate person accepts the role

See Becoming an Executor for more details about the actual process.

Getting Started

Getting started with your executor duties can be challenging, particularly while trying to handle the grief associated with a recent loss, but an executor does have some immediate responsibilities, and there are initial steps you can take to make the overall process easier in the long run.

Some things you likely need to do right away:

- Arrange the funeral

- Secure the assets

- Locate a copy of the will

- And more... (see First Week)

Longer term, it's not uncommon for the entire settlement process to last 6-18 months: some things just take time (while you wait). You also need to be careful about calendar year-end, with respect to various legal and tax filings.

Fundamentally, it is the executor's job to manage and wind down the deceased person's estate, reviewing the will, resolving any debts, distributing assets to heirs, and filing legal paperwork. A somewhat simplified view of the overall process is:

- Arrange Funeral — Burial or cremation, memorial, etc.

- Take Inventory — Estate assets and debts

- Become Executor — Get appointed by the court (if going through probate)

- Send Notifications — Friends and family, social security, credit cards, etc.

- Manage Estate — Plan asset disposition, maintain assets

- Resolve Debts — Payment in full, debt forgiveness

- File Taxes — Decedent income, estate income, inheritance, etc.

- Make Distributions — Distribute net assets to heirs

- Wrap It Up — Finalize estate settlement, including probate final accounting (if applicable)

At multiple stages along the way you may have to file legal and tax paperwork, and while this guide has relevant information, it may be helpful to work together with a lawyer (see Do I Need a Lawyer?). While many estates must go through probate, which is the court-supervised version of estate settlement, this diagram illustrates the steps that generally apply to every estate, whether or not probate is involved.

Like so many things in life, being an executor can become an all-consuming activity if you let it. You can use this guide to get organized and save time.

Key Executor Duties

An executor has 12 key duties when settling an estate, and each duty can require a variety of specific actions, so after reading the general descriptions, be sure to continue reading about the overall process, and the specific individual tasks. See also the overall Executor Guide.

Within the context of managing and winding down a decedent's estate, an executor has the following key duties:

Arrange Funeral

Although not legally required to do so, executors commonly take the lead in managing any funeral. Funeral expenses can be paid or reimbursed from the estate, and a "standard" funeral, including a casket, will probably cost around $6-10K (plus any burial costs, which can be substantial) ... with the caveat that funeral costs vary significantly by region and by service choices. See Funerals for more information.

Collect and Inventory Estate Assets

Aside from potentially arranging the funeral, one of an executor's first duties is to collect and inventory estate assets. This may mean taking physical possession of tangible assets such as jewelry, cars, and homes, as well as gaining legal control over financial assets such as bank accounts and stock portfolios. The sooner you can do this the better (see Protect and Manage Assets below), but assets held by other custodians (such as a financial institution) will usually require you to first be appointed executor by the probate court, which can take several weeks.

Discovering all assets in an estate can be more challenging than you would think, even if the decedent left a seemingly organized list. Over time you may receive account statements in the mail from previously unknown assets, and you may discover additional assets by asking the decedent's lawyer or tax accountant, by perusing the decedent's recent income tax forms, or even performing online searches for life insurance policies, abandoned assets, retirement plans, and more: see Finding Assets for helpful information.

Part of the inventory process is to determine the value of the assets so that taxes can properly be assessed, and so that distributions can be appropriately allocated. Certain types of assets are easy to value, such as the contents of a bank account or shares of stock in a publicly traded company. Other asset types can be a little less definitive, such as a used car or collectible, which you can estimate using public references, or real estate, where you may want to look at the tax assessor's valuation and talk to a real estate agent about sales of comparable properties. Still other asset types can be downright difficult to value, such as artwork or a private business, for which you likely need hire a professional appraiser. See Determining Value.

Initiate Probate (If Required)

Probate is the court-supervised process of administering and settling a decedent's estate ... and how one obtains an official appointment as executor. Not all estates need court involvement, and this guide can help you figure out the requirements for your estate (see Is Probate Required?). In general, an estate will have to go through probate unless it contains only assets that automatically transfer to named beneficiaries (such as IRAs), or if the estate qualifies to use one of the state-specific small estate procedures.

Protect and Manage Assets

An executor must protect and manage estate assets, taking reasonable steps to minimize asset risk. For example, an executor should lock up valuables to prevent theft (or even to prevent well-meaning relatives from taking things "the decedent would have wanted them to have"). Key assets should be insured according to normal practice (e.g., homes, cars, valuable artwork). See also Secure the Assets and Protect Unoccupied Property.

Certain assets require proactive care. For example, if there is a home, you must ensure that it is reasonably maintained (protecting it from fire hazard, damage due to a leaky roof, or even vandals attracted by an obviously abandoned property). If there is a business, you must ensure that it continues to operate (assuming it was not something that depended on the solo efforts of the decedent), possibly managing the business yourself, or hiring a professional manager.

While there are many types of assets, each with their own needs, it's worth mentioning investments in particular. On the one hand, there is a degree of risk associated with any investment, and you have a duty to protect assets against loss (including reduction in value). If the decedent owned some particularly risky stocks, you may want to consider trading out of them into something considered "safe". On the other hand, putting all the investments into cash would mean that the assets would not only "lose value" over time due to inflation, but would fail to grow as expected. As an executor, you need to follow a reasonably safe, prudent investment course. You are not asked to produce exceptional investment returns, but you should aim for and accomplish reasonable returns (with a preference for safety). If you are not an experienced investor, you may wish to consider obtaining professional advice.

Notify Required Parties

There are number of people and organizations you will want to notify about the death, and some of these notifications are time-sensitive. For example, you will usually need to notify various government agencies (e.g., the IRS, the Social Security Administration, the DMV, post office), heirs and heirs-at-law, creditors, life insurance companies, utility companies and other service providers, and more.

Pay Required Taxes

As an executor, you are responsible for ensuring the estate pays all required taxes, including income taxes for the decedent (for the last year of life, plus any previously unresolved years), income taxes for the estate during the period of estate settlement, plus any applicable federal estate taxes, state estate taxes, and state inheritance taxes. In addition, you must continue to pay any local property taxes for property contained within the estate. Note that federal and state taxes have priority over most other claims on the estate, including standard debts. See Paying Taxes for more details.

Resolve Estate Debts

Before making any distributions, you should resolve all estate debts (which may mean paying them off, or negotiating to get them forgiven). You can be held personally liable for estate debts if you make distributions and the estate cannot subsequently pay all its debts, even if the debts were unknown at the time, so it's important to do things in the proper sequence, and to properly notify creditors. See Finding Debts and Resolving Debts.

Distribute Net Assets to the Rightful Heirs

Once you have handled all other estate obligations, you must distribute the remaining assets to the rightful heirs (whether those named in a will, or if there is no will, those entitled to inherit via the state rules of intestate succession). Family Entitlements are an exception to this rule, and have precedence over most other estate obligations, so should often be handled earlier in the process. See Making Distributions.

Account for Results

An executor must prepare a Final Accounting of the estate, showing assets received, income and expenses, changes in assets, and distributions. This report must usually be given to the court if the estate is undergoing probate, and often the heirs. See Wrapping it Up for more information and other closing details.

Settle the Estate in a Reasonable Time

There are few hard-and-fast rules about how quickly you must settle an estate, and while it takes 16 months on average, it is not uncommon for the process to take years (see Settlement Statistics). That being said, you do have a duty to act reasonably, and to try to finish the settlement within a reasonable time. Disgruntled heirs or creditors can petition the court to have you removed if it is perceived that you are not acting in a timely manner. See Failing to Act.

Act in the Best Interests of the Estate

In serving as an executor, you must always act in the best interests of the estate ... even if that is not always in your own best interests. You will likely face numerous decisions that have no clearly "correct" answer, and you will have to use your judgment, even on occasion making decisions based solely on your preferences, which is fine, as long as your choices don't harm the estate (for example, you cannot sell something at below-market prices to a friend). See Fiduciary Duty.

Follow the Law, and Act Ethically

Last but certainly not least, in all cases you must follow the law, and act with the highest ethical standards. While your specific tasks may sound straightforward, there may be a number of laws or expected practices that apply to a given duty, as well as situations that require individual judgement. As an executor, you are not required to achieve perfect results, but you are required to follow the standard of a "reasonable, prudent individual", and it's a good idea to keep excellent records of all your actions, particularly with respect to financial transactions. You may also want to consider obtaining professional assistance for subjects you may not know well (such as real estate valuation, complex investments, etc.). See Fiduciary Duty.

From a high-level perspective, you can visualize the process of estate settlement as follows:

You can think of probate (if required for your estate) as overlay on the diagram above, with the court providing additional rules and individual tasks for each of the depicted steps.

Settling an estate can be complex, and fulfilling each primary duty can require a significant number of individual tasks. These individual tasks often depend on estate particulars, and while some tasks should simply be done when possible and convenient, others have strict deadlines (calculated from the date of death, from the date of other task completions, or even just in terms of calendar year dates).

As a result, while the diagram above looks fairly straightforward, in practice you will find that there is not a simple 1... 2... 3... set of steps you can follow in strict sequential order. Often you will work on one task, work on another, return to the first to do more work, and so on. Consequently, it is very important to stay organized, understand timeline requirements, and keep good track of what you have done, and what remains to be done.

Probate

Probate is the court-supervised process of administering a decedent's estate, ultimately distributing the net proceeds to the rightful heirs (generally in accordance with the will, if a valid will is available).

Probate generally takes more than a year (sometimes multiple years), and involves a number of legal steps. However, certain types of assets automatically bypass probate, and most states have laws that allow qualified estates (usually small) to bypass probate entirely.

There are generally 5 main variants of probate:

- None — If the estate qualifies, you may not need to go through probate at all (see Is Probate Necessary? below).

- Summary — The easiest and shortest form of probate, but usually only for small, simple estates.

- Informal — The most common form of probate, but requires that there are no disputes the court needs to resolve.

- Formal — Lengthier and more expensive, but can resolve disputes. Usually requires the assistance of a lawyer.

- Supervised — Rare and onerous; used when the court finds that an heir needs protection (for example).

Probate laws and rules are determined at the state and county level; there are no federal requirements.

In most cases, if the estate contains only assets that do not require probate (see Probate Exclusions below) or the remaining estate is considered "small", then probate is not required (see Small Estate Probate for specifics by state).

Even if probate is not required, however, some people choose to go forward with an official probate process anyway (see Benefits below).

A number of asset types are generally exempt from the probate process:

- Assets with named beneficiaries, such as

- IRAs, 401Ks, and so forth

- Life insurance policies (unless the beneficiary is the estate itself)

- Funds held in Payable-On-Death (POD) account

- Securities registered in a transfer-on-death (TOD) form

- Real estate subject to a transfer-on-death (TOD) deed

- Vehicles registered in a transfer-on-death (TOD) form

- Jointly owned assets, such as

- Property held in joint tenancy with right of survivorship

- Property held in community property with right of survivorship

- US Savings bond with multiple owners

- Sundry low-value household items

- Assets held in a trust

In most cases, the decision to retain a lawyer is up to the executor: see Do I Need a Lawyer?

Two states (IA, MS) do require an attorney for probate ... unless a small estate settlement process will be used. Similarly, unless a small estate settlement process will be used, FL and TX require a lawyer to represent the executor if there are heirs other than the executor, or if there are creditors involved.

Note that even if the executor does hire a lawyer, the executor will still personally have a lot to do.

Probate details vary significantly by state, and sometimes even by county, but there are many common elements. While it is sometimes possible to settle an estate without going through probate, many of the basic concepts are the same whether or not the court is involved:

Executor Appointment: The first step in the probate process is to get the court to formally appoint you as executor (or personal representative, or administrator, or whatever local term is used). This step requires filing documents with the court, notifying potentially interested parties, and obtaining a probate bond if required. See Becoming an Executor for details, and Probate Forms.

Estate Inventory: You will need to provide the court with an official inventory of the estate (all assets and debts). Often, an initial version of this inventory will be required along with the probate application, but this inventory can be updated later if additional information comes to light. See Taking Inventory.

In Each State: Personal property (such as a bank account or coin collection) is generally probated in the decedent's legal state of residence, but real estate is probated where the property is physically located. Certain classes of personal property, such as vehicles that are registered and titled out of state, may also need to be probated in the jurisdiction where the property is domiciled. If there are multiple real properties in a single state, you can probate them all in the same probate court, but if the decedent owned property in multiple states or internationally, you'll have to go through the settlement process in multiple locations (see Ancillary Probate).

Creditor Notification: It is best practice to notify creditors of the probate process so they know to submit claims, and many states require such notification for estates within their jurisdictions. See Finding Debts.

Family Entitlements: A surviving spouse and other dependants often have rights to the estate that can supercede the terms of a will or even legitimate claims of creditors. In some cases you are legally obligated to inform the spouse of those rights, and in you may be required to wait a certain amount of time to let the spouse decide whether to make any claims. See Family Entitlements.

Debt Resolution: Once you understand the overall financial situation of the estate, you must attempt to resolve all debts. See Resolving Debts.

Tax Payments & Discharge of Personal Liability: You are responsible for filing a tax return for the decedent's final year of life, and for the estate. It is best practice to then apply for a Discharge of Personal Liability (IRS Form 5495) before distributing assets to heirs. See Paying Taxes.

Asset Distribution: Once you have resolved all debts and paid any taxes due, you can distribute the remaining assets to the rightful heirs. See Making Distributions.

Final Accounting & Probate Closing: In general, the probate process concludes with submission and court approval of a "Final Accounting" and a "Probate Closing Statement".

It can sometimes be difficult to determine which court to use for a given estate. The particular type of court that oversees the probate process varies by state: it may be a dedicated probate court, a circuit court, a superior court, a general county court, or something else.

As noted above, remember that real property must be probated in the state in which it is physically located, so you may need to go through probate in multiple states.

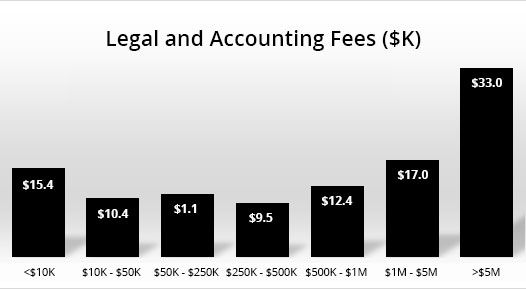

It will likely only cost a few hundred dollars for probate court costs ... and thousands of dollars to pay lawyers, appraisers, and possibly a tax accountant. The average estate spends $12,400 on lawyers and accountants (see General Statistics), and since lawyers and accountants typically charge by the hour, having your information well-organized will save you money over time.

If probate is required, one clear benefit of probate is that you will be following the law. However, even if probate is not required, it can help shield you from potentially unhappy heirs, and it will also get you a document commonly known as your "Letters" (sometimes known as Letters of Authority, Letters of Administration, Letters Testamentary, etc.), which will make it easier for you to prove your authority when dealing with third parties such as banks.

If the estate is not required to go through probate, and you decide not to bother with it, you won't get your "Letters" as described above. Instead, many states will allow you to claim assets using a simple sworn statement ("affidavit") that the decedent has passed away, you are the executor of the estate, and are taking possession of the asset. In many cases, you will have to provide a copy of the death certificate as well.

If the decedent died intestate (i.e., without a will), you will likely have to use an Affidavit of Heirship, which is a document stating the location and date of the decedent's death, and the name and address of all heirs specified by statute.

See Small Estate Alternatives to Probate for state-specific details.

Estate Settlement Statistics

The typical estate at the time of settlement is worth between $50-$250K, with 11% under $10K, and 11% over $1M. Beginning in 2018, only estates worth >$11M are subject to US estate tax, so although many estates are still subject to federal income tax and state taxes, very few are subject to federal estate tax (some estimates place this at < 0.1%).

On average, it takes almost 16 months to settle an estate. Very small estates (<$10K) have a somewhat shorter settlement duration, and very large estates (>$5M) take almost 3 times as long, but in between those extremes, duration is fairly unrelated to size. Roughly 80% of all estates are settled within 18 months.

It takes an executor roughly 570 hours of effort on average to settle an estate. In general, the more valuable the estate, the more effort required, although the data indicates an unexpected spike of effort in the $50-$250K range. Roughly 80% of estates are settled with < 800 hours of executor effort.

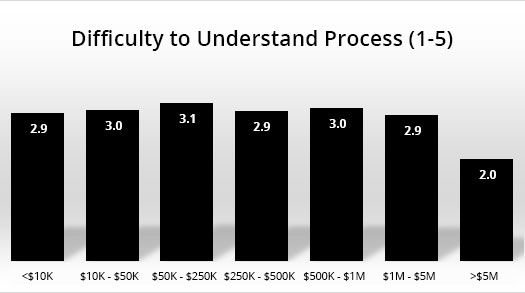

In general, executors feel that the settlement process is neither particularly easy nor particularly difficult to understand, with an average rating of 3.0 out of 5 (5 being “Very Difficult”). Counterintuitively, executors for estates > $5M feel that the process is easy to understand, largely due to increased reliance on professional help.

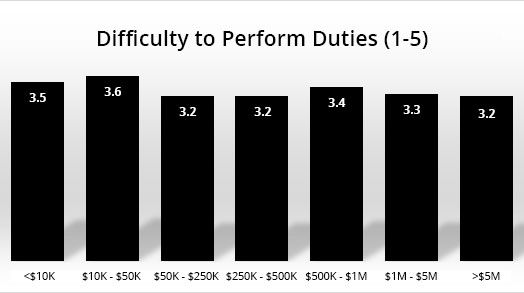

Executors feel that actually performing their duties is slightly difficult, with an average rating of 3.4 out of 5 (5 being “Very Difficult”). Size of the estate seems to have little correlation with perceived difficulty, perhaps due in part to executor expectations in relation to estate size.

The average reported executor compensation was $18K, and the general trend is that the larger the estate, the larger the compensation (with compensation for $10K - $250K estates above trendline). However, executor compensation is governed by laws and court rulings which vary widely by state.

The average estate spent $12.4K on legal and accounting fees, with more spending at the high end of estate values.

Family conflict, sometimes even escalating into lawsuits, is somewhat common during the estate settlement process. Over 44% of respondents had experienced or were aware of such family conflict. For example,

- My wife's family got into a dispute over their parents' estate and never spoke to each other again.

- In my mother's family, there have been two instances of inheritances breaking entire branches of our family apart.

- There was a huge fight over season tickets for the Green Bay Packers. They all took each other to court over it and 9 of them still do not talk to each other.

- Brother and sister not speaking to each other for 10+ years.

- My Dad's brother won't speak to him anymore because he's still mad ... even though it happened 10 years ago.

- My grandmother died and her granddaughters sued. They carried the suit into 9 years of conflict... I hated it.

- After my mother died, the five siblings were to split everything. One brother sued the rest of us and my sister the executrix constantly, and eventually burned up the money in the estate on lawyers we needed to defend us. He decided that if he couldn't run the show, everyone would get nothing, including him. Sad, sad story.

Causes of the conflict varied greatly, ranging from beliefs that the other party stole from the estate, to simple objection to the terms of the will. One common theme was mistrust, often engendered by lack of communication. and 19% were aware of perceived executor misconduct. For example.

- Parent with dementia takes 2 years to pass away-executor/son spends everything before the will can give equal shares to the 3 siblings.

- My dad took my sisters and my inheritance money and spent it.

- When I was 13 my grandma died. As her 1st born & closest granddaughter, I was supposed to get her amethyst ring & a pillow she had. My aunt said she never saw the stuff. A few years later, my mom noticed my cousin wearing the ring. So, auntie just took the ring & lied about it..

- My uncle left me and my mother something in his will, he told us before he died he had and where it was, but my other uncle (executor) took everything from us.

- My aunt stole my inheritance.

- A family member trusted a lawyer more than they should.

- My older sister decided to take everything except my dad's car, golf clubs, and $10000. Now she is putting all three of her children through college and I am struggling to even get a loan.

- My mother made sure her brothers didn't get their inheritance.

- My mother was responsible for distribution of assets, but my aunt took it upon herself to take over that role without our knowledge.

Then there were just the generally unhappy inheritance stories. For example,

- There were more debt collectors than family members interested in the estate... she maxed out all her credit cards and apartment loans when she knew she had only 2 weeks left to live. Next of kin and family members did not want to claim her as a relative because of debt collectors.

- Sister empties house, puts grandson on street, puts grandfather in home, and thinks the estate is hers. Then paperwork surfaces that says grandson receives estate when grandfather dies. Lawyers are battling, driving up costs. Families are greedy, scheming, selfish, immoral, etc, when it comes to money.

- My grandfather by coercion or otherwise gave all of his inheritance to a female college student at Shippensburg University. Shitbag.

- Family members taking items before will has been read.

- When my grandfather passed away he left his home to his children (my father and his siblings). But my aunt took possession of the house after some dispute (we still don't know why) and sold all my grandfather's old antiques and the house as well.

- My three aunts ignored the wishes of my grandfather by selling his cottage to one of the aunts below market value even though he had expressly told them it was to go to my mother (their sister-in-law) as my father had died prior to my grandfather's death. They also ransacked the house and took all of the antiques prior to an estate sale.

- Was contacted by a company that had discovered years later that my aunt owned stock that was not distributed when we settled her estate. I had to reopen the estate, establish an estate checking account, divide proceeds, ad infinitum.

It should be noted that while the above stories are cautionary, many of the respondents had no stories to tell, and felt that things went reasonably smoothly.

Transparent communications with the heirs and good record-keeping help minimize the potential for problems. See also Dealing with Heirs and Executor Fiduciary Duty.

The Unspoken Rite of Financial Passage

Certain events in a person's life qualify as "financial rites of passage": obtaining your first credit card, buying a house, combining finances with a significant other, retirement, estate planning, and so forth.

Dealing with the death of a parent ... or of any loved one ... is life's "unspoken rite of financial passage". For some, the process can involve relatively large sums of money, and important decisions for the future. For others, the amount of money involved may not be a significant factor, but the responsibilities and legal ramifications are still substantial. For all, it is an inevitable occurrence, and yet one for which many are unprepared.

As an executor, you have a fiduciary duty to do the right thing. It is important to follow the relevant rules, keep good records of everything, and behave honorably and fairly. That being said, no one expects you to be perfect, and the standard to which you will normally be held is that of a "reasonable, prudent individual".

There's a reason the executor process isn't completely automated: most estates have certain unique circumstances, and you can and must use your own judgment for a number of decisions. No need to become overly alarmed, but note that executors have been sued and lost for unthinkingly following the advice of their attorneys (for example, Re Estate of Walter and Re Estate of Geniviva). Hiring a lawyer can be helpful, but ultimately you are the one responsible for the proper estate resolution.

Serving as the executor and sorting through the various aspects of the deceased's affairs can be a cathartic way to remember and honor the person's life. Some people use their executor duties to keep busy to avoid grief: that's okay to an extent, but at some point you will have to work through your feelings and come to terms with things. There are a number of ways to deal with grief, and the Additional Resources page links to several grief-related resources.

Beyond grief, some people must sort through new feelings of autonomy, and a certain loss of "protection". This isn't the case for everyone, but for many the loss of a parent exposes them to the world without the comfortable backstop they've always had: someone who would always be there for them, financially or otherwise, even if they never actually needed it. It can be a little frightening to think that one is now truly responsible for oneself, with potentially no one else to step in if help is needed. The good news is that friends, other family members, charitable organizations, and even government agencies can be there to help, and the change is not as drastic as it might appear at first.

In addition to ensuring that legal forms are filed, finances appropriately handled, and distributions made in accordance with the will, you will have to deal with other family members and potential heirs who have their own issues of grief, and desires for various inheritance outcomes. Sometimes this may be as simple as dividing up material possessions so that each person gets their favorite items while still ensuring that values are partitioned fairly, but it can frequently get more complicated than that. Unfortunately, it's not uncommon for heirs or potential heirs to fight about estates. Ongoing communication and transparency about the process can be very helpful to stave off natural feelings of uncertainty and doubt, which can all too often transition into suspicion and accusation. See Dealing with Heirs for general advice.

Given all of the above, if you're not careful, your executor duties can expand to fill all your available time ... for years. It is important to exercise some judgment in this regard as well, and to remember that you need to balance your executor duties with the other priorities in your life.

While people rarely spend much time discussing executor stories before they serve, you will likely find that once you start, many people will open up to you about their own experiences as an executor. Serving as an executor requires time and energy, but it is often a transformational experience that brings the executor even closer to the deceased, while at the same time educating the executor to the realities of end-of-life, and helping them to understand the requirements their own deaths will someday place on their own heirs, catalyzing them to make preparations to smooth their own process. The circle of life continues, and serving as an executor is one of the key milestones in that circle.

Estate Financials

Managing estate financials is at the heart of the executor process, and involves a variety of elements: estate income and expenses, state and federal taxes, asset liquidation, debt resolution, and more.

The executor has a fiduciary duty to manage estate financials for the good of the estate, and to settle the estate in accordance with applicable laws and will directives.

It is important throughout this process that the executor keep excellent records, since some or all of these records may be required by the court, and because the process can otherwise become confusing and error-prone (see Common Executor Mistakes).

Using this guide can help organize this record-keeping. Even if the executor is using a lawyer and/or an accountant, it can be very helpful to all parties to organize and track all this financial information, and in generating a Final Accounting.

An estate typically incurs a variety of expenses:

- Funeral and associated expenses

- Ongoing mortgage payments, property taxes, utility bills, and other property-related services

- Cleaning, repair, and disposal services

- Postage and copying fees

- Legal and financial services

- Other expenses incurred by the executor

Many estates will also generate income during the settlement process, and this must be tracked and reported as well:

- Interest and realized capital gains

- Business and rental income

- Other

Executors normally open a so-called estate account at a commercial bank to handle these transactions (you do not have authority to write checks from a decedent's account, and even if you had power of attorney, that generally disappears upon the decedent's death). While it would be convenient to open such an account immediately, you will almost certainly need to wait until you can provide a copy of the death certificate and an EIN, leaving you in the awkward state of having to pay for any interim expenses out of your own pocket, to be reimbursed once you can get access to the estate assets, or to obtain a loan for the estate. Once you have opened an estate account, you will normally fund it by transferring funds from other estate assets, or even selling certain assets.

Caution: North Carolina treats real estate differently than other states, and holds that title to the property vests to heirs immediately upon death, even though in reality it will take some time to legally accomplish this transfer. As a consequence, executors may not pay for any property-related expenses using estate funds unless authorized to do so by the will or the court.

When disbursing funds, an estate must give preference to its obligations in a defined priority order (see diagram). Certain transfers (such as to IRA beneficiaries) happen automatically outside the control of the estate, and the estate itself must then ensure it has enough funds to pay all taxes, then estate administration costs, then any family entitlements, then any general debts, and with anything left over, fulfill any bequests, and finally distribute the residuary estate. If the estate runs out of money handling one priority, then subsequent priorities are left with nothing.

Note that state law determines which debts have priority over other debts, and some debts (such as funeral expenses) often have priority over family entitlements, but these specifics really only matter if the estate cannot pay all its bills (see Insolvent Estates for more details).

As a general rule, it's probably easiest and best to pay estate expenses directly from an estate account, which you can record via the Cashflow tab as mentioned above.

Sometimes, though, an executor may find it easier to pay out of pocket, and later get reimbursed by the estate. For example, in the early days of the executor process, before the executor has obtained an EIN for the estate and opened an estate account, it may be necessary to pay certain estate expenses (such as a utility bill). And even after you have access to an estate account, sometimes it may just be easier to pay something yourself directly (for example, cash is required, or a third party requires a type of credit card the estate doesn't have).

The executor is also eligible for reimbursement of reasonable travel expenses (which may include airfare and hotel if necessary). The executor can also claim reimbursement for miles driven in his or her own vehicle for estate business, whether driving to the decedent's home for various chores, driving to the bank, or whatever else is reasonably necessary. The Executor Expense table will automatically calculate mileage reimbursement rates for you, using government-approved rates for the relevant dates.

Executors are responsible for resolving estate debts, potentially selling off assets as required to resolve those debts, or simply to make estate distribution more manageable (see Managing Assets).

The executor is responsible for filing and paying (using estate funds) the decedent's final income taxes, the estate's income taxes throughout the settlement period, estate taxes, property taxes, and possibly inheritance taxes. See Paying Taxes for more information about these taxes.

Sometimes an estate needs cash before estate funds are available, or an heir may want access to funds before the estate is ready to make distributions.

An executor should be very careful about taking out loans in advance of estate liquidity: these loans can be costly, and there are often other ways to solve problems. Moreover, an executor should almost never take out a loan to pay an heir in advance; if such payment is desired, this should be solely the heir's responsibility.

With those caveats in mind, here are some resources that may be helpful:

- Finder for Better Decisions — Explains inheritance advances and estate loans

- Inheritance Funding — Source of inheritance loans while waiting for probate to complete

- Probate Advance — Source of estate cash advances

If the estate is more complex or significantly larger than the finances with which the executor normally handles, the executor may wish to consider a financial advisor. Here are a couple of resources that may be helpful:

- Financial Advisor Learning Center — Advice by Charles Schwab on finding an independent financial advisor

- Smart Asset — Source of financial advisors

Taking Inventory

A key job of the executor is to determine all assets and debts related to the estate.

This is easier said than done, even if the decedent left what appears to be a very comprehensive and well-organized set of documents. One thing that can be very helpful is the decedent's most recent tax return, which will usually provide information about both assets and debts (see Obtaining Past Tax Returns). Even if you aren't actively looking, you will likely uncover new assets and debts for quite some time, (you'll receive various mailings, for example). So don't think you're done on the first pass!

Assets include things such as real estate, stocks, mutual funds, jewelry, furniture, cars, and so forth: anything that's worth money. If you aren't sure you are aware of all the decedent's assets, see Finding Assets.

In terms of practical advice, it's not worth it to separately list every single small asset. It's perfectly legitimate to list any significantly valuable asset separately, and just lump the rest into something like "home furnishings", for example. If a brokerage account holds several different stocks and mutual funds, you can just list the whole thing as "Merrill Brokerage Account", for example. If you think you need to list >100 assets, you're probably getting too detailed.

See Determining Value for help with asset valuation.

Debts include things such as mortgages, car loans, large outstanding credit card bills, and so forth. See Finding Debts.

In terms of practical advice, it's probably not worth listing every small utility bill and rent payment as a debt.

Managing Assets

An asset is anything in the estate that has value, whether a house, checking account, gold watch, or furniture. One of your duties as executor is to protect and maintain the estate's assets (see Fiduciary Duty). Ultimately, you will either need to sell some or all of these assets, and distribute the rest directly to the heirs

Before launching into asset sales or distributions, it's best to come up with an overall plan for which assets you intend to sell, and which assets you intend to distribute directly to heirs. If it's helpful, you can mark your high-level intentions (sell or distribute) in the Plan column of the Assets table, and then filter the assets by plan type to see how much cash you intend to generate, and the number of assets yet to be planned.

Please keep in mind that wills sometimes specify that certain assets are to be distributed to certain heirs. You can mark these bequests by clicking the Distributed column for the given asset in the Assets tab and filling out the Distribution dialog that appears (see Manage Distributions). However, not all such bequests can be honored: sometimes the asset is no longer part of the estate; sometimes the bequest conflicts with local law (e.g., community property); sometimes the asset must be sold (as a last resort) in order to pay estate debts.

Certain items are not passed through a will, such as life insurance, property held in joint tenancy or community property with the right of survivorship, funds in an IRA or 401K for which a beneficiary was named, stocks held in a transfer-on-death account, and so forth. You can choose to list these items as assets to help you keep things organized, but remember to create a Distribution for each with the "Reason" identified as "Beneficiary".

As the executor, you may decide to sell an asset for a variety of reasons: you may want to raise cash in order to pay off debts, you may think the estate would achieve better financial performance with the funds from that asset invested elsewhere, or you may just want to make things easier when it comes time to partition the estate (e.g., it's easier to give someone 20% of a cash account than it is to give one person a car, another a diamond necklace, and somehow have it all work out to be equitable).

A home is often the most valuable asset in an estate, and this Homelight article on selling a decedent's house has some useful advice about the overall process.

It's common to hold an estate sale to liquidate a variety of household and other items that heirs do not want. There are 3 main approaches to estate sales:

- Garage Sale: If there are only a limited number of inexpensive items to sell, you may try to do this yourself as a kind of super "garage" sale (see PostMyGarageSale.com, for example).

- Professional Auction: For larger estates, you can hire a professional auctioneer to run an auction at your location, or, if the estate isn't overly large, it may be better to have the auctioneer hold a larger auction at their site with multiple sources of assets, attracting even more potential buyers. You can find auctioneers at the National Auctioneers Association.

- Estate Liquidator: The easiest approach is to hire an estate liquidator to handle the whole thing, but of course, you will pay for that ease. The 3 main sources of estate liquidators are EstateSales.org, EstateSales.net, and The American Society of Estate Liquidators. In addition, MaxSold is North America’s largest individual liquidator, with many locations and over 500 employees.

It's also common to sell individual assets through other channels, for example taking jewelry to a jewelry store, selling precious metals through a broker, or selling a car to a used car dealer.

When using a professional seller, it's prudent to do a little research, talk to more than one service, check references, and when dealing with estate sales, have the service visit the estate so everyone has a common understanding as to what is being sold before finalizing any deal. Be sure you carefully read and understand any contract (and insist on one when dealing with an estate sale).

Note that if the estate is going through probate, you may first need permission from the court before selling certain types of assets, or in some cases, any assets at all.

Some assets are inherently worthless: hard-used furniture, frayed clothing, old newspapers, piles of junk, etc. If you cannot sell an item, and no heir wants it, you may have to pay someone to dispose of it (particularly when cleaning out a residence).

Be careful about giving things away to charities. Unless the will specifically empowers you to do so, you do not have the right to give away items of value, and charities won't generally accept things that are worthless.

If the will provides for charitable donations, you should handle them as normal asset distributions, to an admittedly special type of "heir".

If the will does not empower you to make charitable donations, and the estate contains items of value that no heir wants, one way to work around this donation restriction is to officially distribute the items as dictated by the will or the court, on paper, and then with the receiving heirs' permission, arrange to donate the items to charity ... in the heirs' names (from a legal and tax perspective, those donations will come from the heirs, not the estate).

If you don't sell or otherwise dispose of an asset, ultimately you will need to distribute it to an heir (or multiple heirs). See Making Distributions.

Note that an authorized donation to a charity is just another type of distribution, in which the charity is the "heir".

Dealing with firearms can be a bit complex, and depends on federal, state, and local regulation, but in general an executor can distribute a typical firearm to any close relative of the decedent, as long as the recipient is not legally prohibited from possessing it.

- NFA Firearms: Certain weapons are regulated by the National Firearms Act (NFA), including fully automatic weapons, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, and silencers. These weapons and accessories must be registered with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), and any distributions or sales must be done according to ATF rules.

- Gun Registration: A few jurisdictions (such as NY and WDC) require registration for more common types of weapons, although an executor usually has a short period in which to possess and then distribute a firearm without registering the gun himself or herself (in NY, this is 15 days). You should check local rules.

- Prohibited Persons: Generally speaking, you cannot give a weapon to a person who is legally prohibited from possessing it, such as someone has been sentenced to more than a year in jail, dishonorably discharged from the armed forces, or judged mentally defective (see ATF Prohibitions for a more complete federal list, and note that some states impose additional restrictions, such as restrictions for minors). However, some states, such as NJ (see N.J.S. 2C:58-3j do allow prohibited heirs to take possession of a gun for up to 180 days so they can lawfully sell or otherwise dispose of it.

- Heir Responsibilities: Note that some states require the recipient of a firearm to obtain and possess a firearm license, to register the firearm, and/or to take a gun safety course.

- Interstate Transfer: An heir can legally transport firearms across state lines subject to certain restrictions, such as keeping the weapon unloaded and in a locked container, out of easy reach of anyone in the vehicle, and being legally able to possess the weapon in the starting and final jurisdictions (see 18 U.S. Code § 926A). If flying, contact the airline for their procedures.

- Sales: If selling a gun, a number of states require that private individuals perform a background check on a prospective buyer (usually through an FFL dealer), including CA, CO, CT, DE, DC, IL, MA, MD, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OR, PR, RI, VA, and VT. In fact CA, DE, DC, and OR require the sale itself to be done via an FFL dealer.

- FFL Dealers: Perhaps the legally safest way to transfer or sell a firearm is via a gun dealer with a Federal Firearms License (FFL), who can help you fill out any required forms, hold the gun for you, perform any background checks, and then release the gun into the possession of the recipient when everything is complete (find a local FFL dealer).

See also Gun Laws by State.

Resolving Debts

To "resolve" a debt means to pay it off or otherwise deal with it so that the estate no longer owes anything for it. To be completely safe, you should resolve all debts before distributing any assets to heirs (although in practice, you may not need to follow this strictly if the estate is clearly worth more than it owes).

First, note that if a creditor fails to contact the estate within the local state regulatory deadline period (typically 3-9 months after publication of a probate notice), the debt is barred and the estate has no legal obligation to pay the debt. See Statute of Limitations and Claims Deadlines.

Also note that not all apparent debts are valid. You may be contacted by unscrupulous parties seeking to defraud the estate, or even just organizations with flawed record-keeping. You should be careful to make sure the decedent did actually owe the money, and that he or she didn't already pay it.

Although debt resolution generally has priority over distributions to heirs, there are some state-specific exceptions which protect a surviving spouse and children (see Family Entitlements). When considering how and whether the estate can pay all its debts, be sure to first subtract any such priority entitlements from the estate.

Eventually, the estate will have to pay all its valid debts ... unless the estate owes more than it is worth, in which case not everyone will get back all the money owed.

It may be necessary to sell certain assets in order to raise cash so that these debts can be paid. Try to avoid selling assets the will specifically bequeaths to certain heirs, and in fact, it makes sense to have a plan for what you are doing with ALL the assets before you start selling off some here and there. Of course, if it's just selling a few shares of stock or other basically liquid assets, it's not a big deal.

Note that you may want to pay special attention to medical debts, since the estate must pay these within one year of death in order to be able to deduct them on the decedent's final income tax return.

Aside from the big debts, there will also almost certainly be some debts it's best just to pay as they come due, such as the electric bill.

Be aware that IRS Publication 559 states that the executor of an estate that is unable to pay a tax liability of the decedent or of the estate is personally responsible for those taxes if he or she had notice of such tax obligations or failed to exercise due care in determining if such obligations existed before distribution of the estate's assets and before being discharged from duties.

Federal tax debts are considered senior to most other debts, and under 31 USC section 3713(b), the executor is personally liable for any unpaid taxes of the decedent up to the amount of any other debts the executor did pay (see CPA Journal for additional details). IRS IRM §5.17.13.5 acknowledges that courts have held that funeral expenses, estate administration costs, and some family entitlements do have priority over taxes.

If the estate owes more than it is worth, it is considered "insolvent".

You should strongly consider seeking legal help to resolve an insolvent estate, since there are a number of legal statutes governing who should be paid and how much. Details vary by state, but in general an estate must pay debts in the following order of priority:

- Funeral expenses

- Estate administration costs

- Taxes

- Other general debts

Only after arranging to resolve all debts, can you distribute assets to heirs (see Family Entitlements for limited exceptions).

When an estate is insolvent (or near-insolvent), negotiation for debt forgiveness is very common, since the debt-holders may end up with nothing if they don't agree to a lesser amount (see Debt Forgiveness below).

It's common for some debts to be completely or partially forgiven after death, especially if the creditor believes that the estate may not have enough money to pay all debts, and that if the creditor doesn't agree to forgive some of the debt, the other creditors will be paid first and there may not be enough money left at the end to pay to anything to the creditor at all.

When some or all of a debt is "forgiven", that means that the person to whom the money was owed has agreed to reduce the size of the debt. You should get any such agreements in writing. You should also be aware that the amount forgiven is considered taxable income to the estate, and that big corporations such credit card companies will almost certainly report these amounts to the IRS.

Of course, few creditors are going to volunteer to forgive their amounts; you will need to negotiate with them if you wish to get anything reduced. If you have hired a probate attorney, this may be something you delegate to them, since they're used to it.

If the decedent (or later the estate itself) has loaned money to other parties, those loans are considered assets of the estate. The normal role of the executor is to attempt to obtain repayment for those loans so that the funds can be distributed to the heirs. It may sometimes be preferable to attempt to transfer the debt arrangement to one or more heirs as part of the inheritance process, in case collection at the moment is not practical. And if the debt appears uncollectible, you may end up having to writing it off.

Not every financial obligation of the estate is an "official" debt, and there are certain informal obligations that continue to accrue during the settlement process, such as insurance premiums, property maintenance, utility bills, and so forth.

While it may make sense to wait to pay most debts until the executor has a clear picture of overall estate finances, the executor also has an obligation to protect the assets of the estate, and failing to pay some of these bills in a timely manner may result in unwarranted harm to the estate. For example, failing to pay a utility bill may result in frozen pipes bursting, failing to make a mortgage payment may result in foreclosure, failing to pay insurance premiums may be problematic in the case of theft or fire, etc. The executor should use common sense about the overall situation, and within the confines of the law, act in the best interest of the overall estate.

See also Taking Inventory and Finding Debts.

Paying Taxes

There are a number of tax forms you may need to file in your role as executor. This Guide will help you determine which tax forms are applicable and their due dates, listing them in the Tasks tab.

An executor is responsible for filing final personal income tax returns for the decedent. These returns are due at the normal time (typically April 15 of the year following death), but only cover the preceding year until the day of death (after which, the estate becomes responsible and must submit its own tax returns). IRS publication 559 provides federal instructions for this, but it's generally easier just to use Intuit TurboTax® or a tax accountant.

If the decedent had not yet filed tax returns for the year previous to his or her death (imagine that he or she died on January 15), then you are responsible for filing those previous year returns as well, by their normal due dates.

If the decedent already filed his or her taxes for a previous year and a federal refund is due, you can collect it by filing an IRS Form 1310 for the appropriate year. Note that any state refunds are taxable by the federal government, and so could be a taxable event for the estate.

Filing considerations:

- Minimum Income: As with any taxpayer, income tax forms generally need to be filed only if the decedent earned more than a minimum amount during the year, as set by federal and state law (see federal filing tester).

- Medical Deductions: If the decedent incurred large medical costs in the year of death (this is common), remember that you may be able to deduct much of those expenses (see IRS medical deduction overview, and MarketWatch explanation). To qualify, the decedent must have actually paid those expenses before death, or the estate must pay them within one year of death. Alternately, if the estate is large and owes estate tax (this is uncommon), you can instead deduct final medical expenses on the estate tax form, which usually saves more money.

- Surviving Spouse: If the decedent is survived by a spouse who has not remarried, then the final income tax filing can be made as a joint return (counting the decedent's income and deductions only through the date of death), which usually results in a lower tax bill than filing separate returns. Note that under certain circumstances, the surviving spouse may also be able to continue filing "joint" returns for an additional 2 years (see IRS Tax Benefits for Survivors for details).

- Revocable Living Trusts: If the decedent held a living trust, income from that trust during the portion of the tax-year in which the decedent was alive should be reported on the the decedent's income tax return, just as it was during prior years of the decedent's life. Once all owners of a revocable living trust pass away, the trust becomes irrevocable and is considered as a "taxpayer" in its own right, responsible for filing its own income taxes going forward. Of course, this then becomes the responsibility of the trustee(s), not the estate executor (see Trusts).

An estate must file a federal IRS Form 1041 every year it earns over a minimum amount (~$600) until you completely wind down the estate. If you file a federal form, you must file the corresponding state form.

If the estate contains real property, you must pay any relevant property taxes until the property is either sold or distributed to the heirs. Property taxes are often due in two installments during the calendar year; due dates vary widely by jurisdiction.

Note that paying property taxes in North Carolina from estate funds requires explicit authorization by the will or the court, since real property in NC is considered to immediately vest to the heirs (even though in reality the executor retains control throughout much of the settlement process).

As mentioned above, income from a decedent's living trust must be reported on the decedent's annual personal income tax return, up until the point of death. After death, income from such a trust starts accruing to the benefit of the trust beneficiaries, and the trust must report any income it distributes via Federal Schedule K-1s, which must be mailed by March 31 of the year following the decedent's death (and every year thereafter that the trust distributes income). Any income not distributed in a given year must be handled via the trust's own federal (Form 1041) and state tax filings. Of course, managing a trust is the responsibility of the trust trustee, not the estate executor (see Trusts).

If you are dealing with a large estate, you have 9 months from the time of death to submit a federal Form 706. This form is required, for example, if the gross value of an estate whose decedent died in 2021, plus any inflation-adjusted taxable gifts made by the decedent during his or her lifetime, exceeds $12.06M. For decedents who died in earlier years, the limits were $11.18M in 2018, $11.4M in 2019, $11.58M in 2020, and $11.7M in 2021. (see Sample Estate Task: Submit Form 706 for your particular estate requirements). Just because you have to file this form does not mean the estate will owe any taxes, since taxes are calculated on estate net value. A 6-month extension is available if requested prior to the due date and the estimated correct amount of tax is paid before the due date.

Even if you are not required to file a Form 706, it may be to the advantage of any surviving spouse to do so, since filing a Form 706 grants any unused exemption amount to a surviving spouse. For example, if someone died leaving behind a $3M estate, and the exemption amount that year was $11M, a surviving spouse would gain an additional $8M for his or her eventual exemption amount, potentially reducing his or her eventual tax burden.

If you file a federal Form 706, you must also file IRS Form 8971 identifying heirs, the inherited property, and its valuation. This additional form must be delivered by the earlier of 30 days after the estate tax return is filed, or 30 days after the estate tax return was due to be filed (if you missed the 706 deadline).

If the estate does owe federal estate tax, note that you have the option to establish an Alternate Valuation Date, which which basically allows the executor to define the value as of 6 months after death (if doing so would reduce taxes owed), as opposed to the value on the date of death. You must make this election within one year, and it is irrevocable. See Federal Statute 26 USCS § 2032.

You may also have to file a state estate tax form if the decedent lived in a state with its own estate tax (in 2021: CT, HI, IL, MA, MD, ME, MN, NY, OR, RI, VT, WA, and WDC).

If you must file a federal Form 706, it's also a good idea to request an Estate Tax Closing Letter from the IRS (see Tax Closing Letter Request for details), and it may be required if the state also imposes estate taxes. You must wait at least 6 months after filing Form 706, and then call (866) 699-4083 or fax (855) 386-5127. Alternatively, IRS Notice 2017-12 explains that an account transcript can now be used in place of a Closing Letter. Submit IRS Form 4506-T to request such a transcript (see IRS Transcript Request for instructions).

See IRS answers to frequently asked questions about the estate tax, and see Wikipedia on Estate Taxes for an interesting summary.

Unlike an estate tax, which is a tax levied on the overall estate, an inheritance tax is a tax levied on amounts distributed to individual heirs. There is no federal inheritance tax, but a few states do enforce their own inheritance taxes (in accordance with the decedent's state of residence, not the address of the heir). Inheritance taxes typically vary by the relationship of the heir (e.g., child, spouse) with the decedent, and it is generally the estate that must pay the tax. If applicable, the inheritance tax form must be filed within 6-18 months, depending on the state.

While not required, you can submit IRS Form 5495 to shorten the period during which you may be personally liable for underpaid federal income, gift, or estate taxes.

Normally the IRS has 3 years to after the submission of any tax return to assess it and request payment of any determined deficiency. Form 5495 shortens this period to 9 months (6 months if you are a professional fiduciary). You are not required to wait for the expiration of this period before making distributions; just be aware that you could be personally required to make up for any underpayments if the estate does not have enough funds to pay, due to your earlier distributions.

You can only apply Form 5495 to tax forms you have submitted, not future ones, so you can wait until all tax forms have been submitted before filing Form 5495, or you can submit additional copies of Form 5495 over time as you file new tax forms.

Determining Heirs

The executor is responsible for appropriately distributing the net estate to the rightful heirs. In many cases, the heirs are clearly spelled out in a will, and this task is simple. Just enter the requested information in the Heirs tab (see Define Heir for instructions).

There are several overlapping terms used to refer to people who inherit from an estate:

- Heir: Usually someone who is related to the decedent, and would normally inherit from the estate even without a will.

- Devisee or Legatee: Someone specifically named in the will. Historically, a devisee inherited real estate, and a legatee inherited personal property (including cash).

- Beneficiary: General term for someone who will inherit from an estate, but also specifically used for asset classes (such as a 401K) that bypass probate and go directly to the person named.

To keep things simple, this guide uses the common term "heir" when referring to anyone who will inherit from the estate, and additionally uses the term "beneficiary" when dealing with assets that automatically bypass probate.

If an heir died after the decedent, then that heir's estate simply inherits whatever that heir would have inherited.

If an heir died before the decedent, then the following rules apply in priority order:

- If the will names an alternate recipient, then the alternate receives the inheritance instead.

- If the recipient was not specifically named, but was instead simply part of a group (i.e., "my children"), then the remaining members of the group split the inheritance among themselves.

- Some wills specifically state that any bequest to a pre-deceased person should instead become part of the residuary estate, and thus be distributed to the residuary heirs along with everything else.

- Otherwise, the particular state's "anti-lapse" laws may apply, generally assigning the inheritance to the dead heir's blood relatives, in a particular priority order. If you are uncertain as to who should inherit in this case, you may want to speak to an estate lawyer.

- If none of the above conditions are met, then the property becomes part of the residuary estate, and is distributed to the residuary heirs along with everything else.

- If there are no surviving residuary heirs, and the state's anti-lapse statute did not apply (perhaps because there were no qualified blood relatives of the deceased residuary heirs), then the residuary estate is distributed according to the state's laws of intestate succession (as if there were no will).

If there is no valid will, then the estate is considered intestate, and must be distributed according to state law in the decedent's legal state of residence. You don't necessarily need a lawyer in such cases, but one can provide reassurance that you are doing the right thing.